The Art of Value: Rethinking the Market Through Taste, Trust, and Time

In a market where emotion meets investment, taste collides with data, and trust is the true currency, The Art of Value explores the evolving nature of collecting through the eyes of Megan Corcoran Locke, Director at ArtTactic. From shifting definitions of value and the rising role of works on paper to the quiet power of institutional influence and the next generation’s eclectic, impact-driven approach — this article unpacks the complexity, charm, and contradictions of today’s global art market.

In an age where markets are measured in metrics, the art world remains a rare paradox: governed by data, yet deeply emotional; driven by taste, yet tethered to value; cloaked in opacity, yet founded on trust. Few understand this complex terrain as well as Megan Locke, director at ArtTactic, a leading independent art market research firm.

Having begun her career in the precise, fast-paced world of fixed income trading, Locke's pivot to the art world was both personal and profound. "I decided I wanted to sell paintings, not bonds," she recalls. Now, at the intersection of research, relationships, and the ever-shifting landscape of global collecting, Locke provides clarity in a market long defined by mystique.

Defining Value in a Subjective Market

"Value is such a funny concept in art," Locke begins. "Is it emotional, aesthetic, historical, or financial?" For centuries, art collecting was a personal pursuit, guided more by ethos and taste than ROI. Paintings were acquired because they resonated emotionally, spoke to a collector's sensibilities, or symbolised intellectual and cultural capital. Today, however, art is increasingly viewed as an asset class.

With family offices, wealth managers, and private banks incorporating art advisory services, the market has institutionalised. Value now often means financial return, risk management, and long-term performance. Yet Locke argues that at its core, value in art rests on a shared belief in significance. "It’s the assumption that an artist or work matters now, and will continue to matter. That is what translates into longevity, and ultimately, financial return."

Historically, collectors were guided more by ethos than economics. A painting wasn’t just a potential asset — it was a reflection of taste, of cultural belonging, of identity. But today, as family offices and private banks increasingly offer art advisory services alongside equities and alternatives, value has taken on a more financial cast.

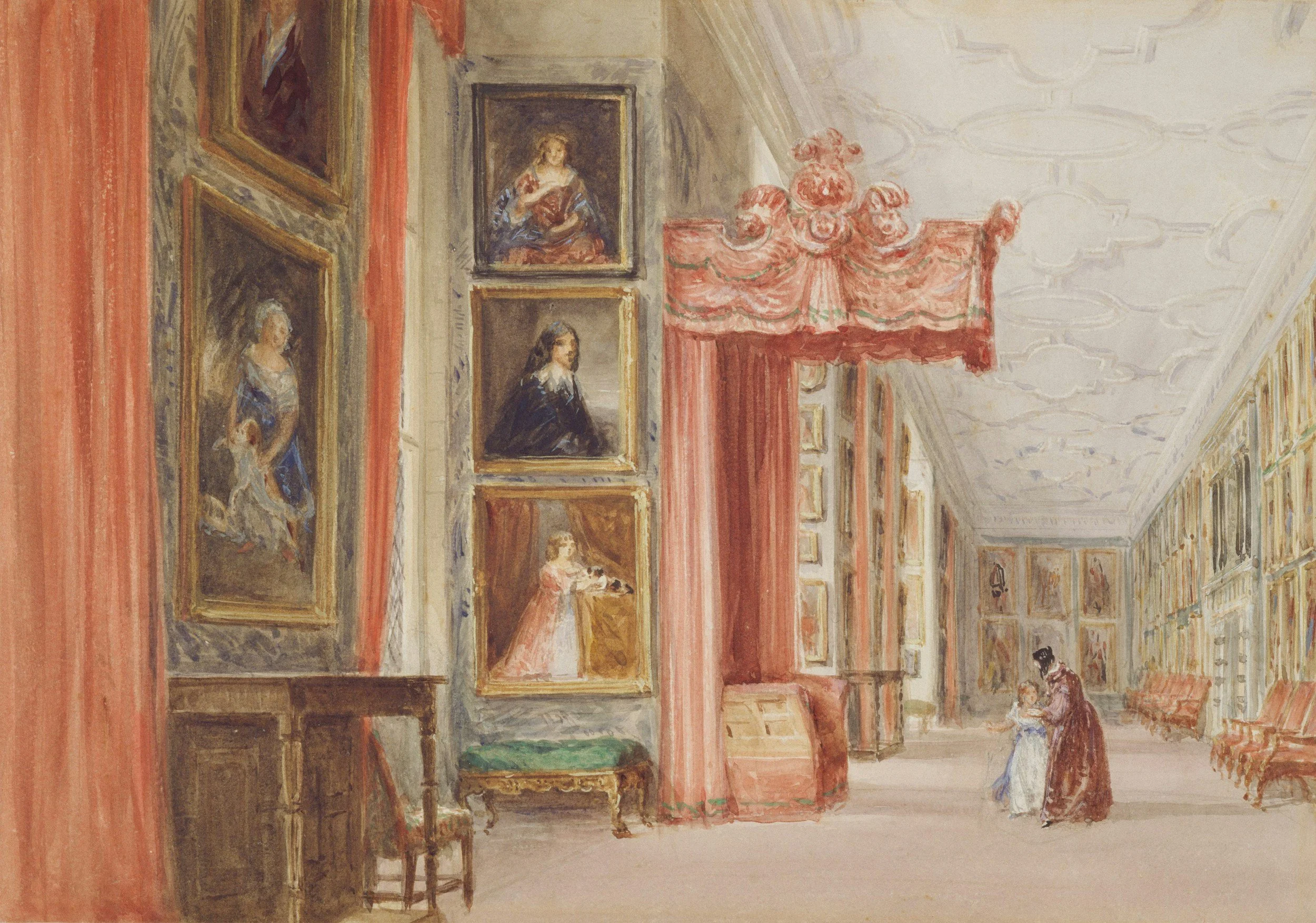

The scarcity of works by historically canonised artists such as Old Masters has nudged collectors towards alternative areas. Locke outlines a market shift through time: from the Italian Renaissance, to 18th-century French and Dutch 17th-century works, and now towards 19th-century painters, particularly those underrepresented in the canon.

Take Marlow Moss, for instance. A British modernist artist aligned with Mondrian’s movement, her work recently fetched $500,000 at auction — double the estimate. "Compare that to a Mondrian, which sold for $47 million," Locke notes. "There’s a significant value gap despite shared aesthetic and historical resonance." This highlights the potential in uncovering undervalued artists whose time has come.

From Botticelli to the Baltic: Following the Drift of Demand

The art market does not reward stasis. What once was prized — 15th-century Italian panels, say — is now mostly off-market, locked away in museum vaults or private collections. As such, taste shifts in response to scarcity. “It’s all supply,” Locke notes. “If you can’t get a top-tier Botticelli, you start to look for the next great story.”

Over time, the lens has moved: from the Italian Renaissance to the French Rococo, to the Dutch Golden Age, to, more recently, the 19th-century Scandinavian school. “Danish artists like Hammershøi are having a moment,” Locke says. “You can trace it back to exhibitions at the Met, the Getty, and Paris in 2022 and 2023. And now, suddenly, they’re appearing in the evening sales.”

The art world, in this way, is cyclical — propelled forward by institutional programming and scholarly rediscovery. Locke points out that while academia has traditionally been kept separate from commerce, the two fields are now in constant dialogue. “The old ideal was to preserve the sanctity of the museum,” she explains. “But the reality is that institutions and the market need each other. The ecosystem is symbiotic.”

Museums as Market Catalysts

Institutions play a powerful, if often subtle, role in shaping the market. Locke and her colleagues at ArtTactic have identified a recurring trend: museum exhibitions tend to precede market growth in particular segments by two to three years.

Recent momentum in 19th-century Danish art is a case in point. Major exhibitions at the Met, the Getty, and museums in Paris showcased artists like Vilhelm Hammershøi, long admired by specialists but underrepresented at auction. Fast forward to 2025, and a surge of Danish works appeared in London sales.

Traditionally, the art world maintained a strict divide between academia and commerce. But that boundary is increasingly porous. Museums now buy at auction; dealers curate with institutional visibility in mind. "It’s a symbiotic ecosystem," Locke observes. "Academic integrity matters, but both sides need each other to sustain vibrancy and innovation."

Trust: The Currency of the Private Market

More than half of the art market is private. Unlike the auction world, where sales are public and prices searchable, the gallery and dealer world functions largely on conversation — and trust.

“For people just entering the art world, it can be overwhelming,” Locke says. “There’s so much information, and very little of it is accessible unless you know where to look or who to ask.” This makes personal relationships — with advisors, dealers, curators — essential. In this sphere, data is scarce, and trust is paramount. "Buyers rely on relationships," Locke explains. "Trust becomes everything."

Locke warns against high-pressure tactics. “If someone’s telling you to act right now, that’s a red flag,” she says. “Auctions move fast, but otherwise, a good advisor should encourage space to reflect.”

Transparency is another marker of trust. Dealers unwilling to share the history of a piece — or who obscure its auction past — raise concerns. “Yes, everyone needs to make a profit,” Locke acknowledges. “But the best in the business are thinking long-term. They want to build relationships, not just close a sale.”

For newcomers, Locke suggests beginning with auction house previews. "They’re public, welcoming, and educational. The price estimates are there. It’s a great place to ask questions without pressure."

The Role and Limits of Data

ArtTactic distinguishes itself by remaining wholly independent: it does not trade art, nor advise on transactions. This allows its data to remain impartial. "We're not trying to influence the market, only to interpret it with integrity," Locke says.

Still, data has limitations. Market outcomes can be capricious — influenced by global politics, auction timing, or simply who’s in the room that day. "Data gives a foundation, not a prophecy. It needs to be paired with expertise, gut instinct, and taste."

Moreover, confirmation bias is a constant threat. "Data can tell many stories. That’s why independence matters. Our job is to help people build their own narrative with reliable information."

Works on Paper: Value, Access, and Intimacy

Among the most vibrant segments in today’s market are works on paper — a category that includes original drawings, prints, and editions. Locke is a passionate advocate. "They’re more accessible in price, and they allow for mistakes. You can learn without taking enormous financial risks."

Beyond economics, there's a sensory dimension to these works. "Drawings often feel more immediate. You see the artist’s touch, the thinking process. They are intimate, approachable, and romantic."

This category also allows collectors to acquire blue-chip names at a fraction of the cost. Their portability, affordability, and emotional resonance make them an ideal entry point for new collectors and a sophisticated option for seasoned ones.

The Next Generation: Cross-Category Collecting

New wealth is rewriting the rules. Younger collectors are less bound by genre or medium. Their collections reflect a hybrid taste: a mix of painting, photography, sculpture, digital, and design. "They are more likely to collect across categories, guided by passion rather than academic cohesion," Locke says.

Taste-driven and socially conscious, these collectors also bring a sense of patronage. Many support living artists directly, viewing art buying as a form of cultural impact investing. "It’s about nurturing talent. Helping artists maintain studios, supporting their growth. That’s a beautiful part of the ecosystem."

This approach echoes older models of patronage, but it is more democratic and dynamic. In a moment where cultural institutions are under pressure, the collector as benefactor feels particularly resonant.

Advice for Collectors: Look and Ask

Locke’s most enduring advice is also the most elegant: "Go and look. Train your eye."

Visit museums, preview sales, and exhibitions. Develop an internal compass for what speaks to you. "It takes time to learn what you truly love versus what’s simply fashionable."

Equally vital is curiosity. "Ask questions. Whether at a fair, a gallery, or a preview, don't hesitate. Professionals love to talk about art. That’s how you find people you trust."

A Market in Motion

Despite headlines forecasting doom, Locke remains measured. The frothy highs of recent years have given way to recalibration. "It’s not that the market is dying. It’s evolving. The volume of sales is steady, but the value is more modest. That’s not collapse — it’s correction."

Collectors are more discerning, more strategic. The art world is adapting. And in that shift lies opportunity.

In the theatre of the art market — where taste meets transaction, and connoisseurship meets commerce — perhaps the greatest truth is this: value is never fixed. It evolves with us, shaped by time, taste, trust, and the irreducible humanity that art, at its best, exists to explore.